Money, medicine and poor record keeping

In Nigeria, what percentage of our government owned medical institutions take payments from drugs producing companies? How many physicians take payments from drugs companies to prescribe certain drugs to patients? Are there laws supporting such disclosure of financial information or laws prohibiting this forms of relationships?

These were questions I mentally asked myself while having a chat with Propublica’s Ryann Jones and Ken Schwencke at their New York office in February in a bid to learn from Propublica’s successes, one of several learning opportunities availed to me after emerging winner of Quartz Africa’s Atlas for Africa competition in November 2017. The questions had never occurred to me, never, not before now.

Ryan had introduced and talked about the Dollars for Docs app, a database of payments to doctors and teaching hospitals from pharmaceutical and medical device companies made between August 2013 and December 2015. Consisting of 15 categories, the app included promotional speaking, consulting, meals, travel and royalties, while physicians included were medical doctors (MD), dentists, osteopaths (DO), optometrists, podiatrists and chiropractors. Users could also search by ‘teaching hospitals’.

For data on industry payments to doctors, Propublica relied on the federal government’s Open Payments system. To determine which physicians practiced at which hospitals, Medicare’s Physician Compare data was used. For information about a hospital’s details, ownership and characteristics, Medicare’s Provider of Services file and data from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey 4,815 hospitals were analyzed, of which 2,241 were included in the tool.

For data on industry payments to doctors, Propublica relied on the federal government’s Open Payments system. To determine which physicians practiced at which hospitals, Medicare’s Physician Compare data was used. For information about a hospital’s details, ownership and characteristics, Medicare’s Provider of Services file and data from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey 4,815 hospitals were analyzed, of which 2,241 were included in the tool.

The platform was built on layers upon layers of already existing and accessible data. We don’t even know how many doctors there are in Nigeria, and there is no such thing as a platform to track payments by drug companies or their reps and lobbyists to facilitate and promote the use of particular brands of medications. There is no law that protects patients from vulture drug firms and their reps, however some medical professionals I spoke to say the only guiding principle here is ‘ethics’. Just ethics.

Propublica’s analysis revealed that most doctors receive payments, and that these doctors on average, are more likely to prescribe a higher percentage of brand-name drugs, just as it happens in Nigeria where physicians get all expense paid trips to health conferences only to return and champion drugs made by their sponsors, according to another medical expert.

Could we in Nigeria develop something similar I thought, would it be easy tracking and documenting payments physicians receive from drug companies, the sum of those payments, and the different companies that made the payments?

Lack of data and the problem of disclosure.

In Nigeria, for such data to be disclosed, there has to be a law binding it, a system to support it. The disclosures on Dollars for Docs were made under the Physician Payments Sunshine Act, which requires manufacturers of drugs, medical devices, etc. covered by the three federal health care programs Medicare, Medicaid, and State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) to collect and track all financial relationships with physicians and teaching hospitals and to report these data to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Data is a major problem in Nigeria. We don’t have that kind of data readily accessible. The little available data lies dormant, largely due to lack of skill to mine it for insights, fear of the unknown, a lack of cognition of the huge returns from making decisions with data, and poor data collection and management practices. Most of Nigeria’s medical data is locked away in legacy infrastructures and medical files on shelves across medical institutions and there is little or no will to have them digitized.

The aim of the Payment Sunshine Act was to increase the transparency of financial relationships between health care providers and pharmaceutical manufacturers and to uncover potential conflicts of interest. The Nigerian government at the moment is very shy about transparency and innovation in healthcare and does not have such a law. The closest to Medicare’s Physician Compare data Nigeria has ever had is Dodgy Doctors built by SaharaReporters in partnership with Code for Nigeria in 2015.

The platform uses Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN) data to help citizens quickly and easily verify accreditations of their doctors, and if they are in ‘good standing’ with the medical authorities. However days after the launch of Dodgy Doctors, the MDCN in a press release labelled the data on the platform as fake, saying they will soon create a link on its web portal that will aid citizens determine whether a practitioner is genuine or not.

Three years down after the hot talk, MCDN actually created the link tagged ‘MCDN Quack-list’, but as of the time of writing this article, the page is empty, there is no data whatsoever on it. In 2013 it was reported that the Nigerian government would launch an online database of health facilities and specialists. The year is 2018, I am still yet to come across such a database. These are perfect examples of how unserious the government is towards healthcare innovation and data.

Instability, inefficient policies and political will

Marred by high prevalence of maternal and child mortality, disease outbreaks and series of industrial actions by its workers due to unpaid salaries and other administrative challenges, Nigeria’s health sector is highly unstable. Currently Nigeria’s healthcare system is among the lowest, ranking at 187 out of 190 in World Health Systems ranking by WHO. An all-time low record.

The poor rankings, lack of sufficient policies and the seeming lack of will to improve despite his investment of over $1 billion to Nigeria’s health system were the reasons world’s second richest man Bill Gates recently criticized Nigeria’s education and healthcare policies. Gates called the current plans in education and healthcare ‘inadequate and not good enough’. For him, an improved healthcare will be an engine of growth not just for Nigeria but for all of Africa.

Dollars for Docs dataset contained nearly $6.25 billion in medical industry payments made to more than 800,000 physicians. To embark on such a project in Nigeria, data transparency and literacy levels across all government owned medical institutions, health related government agencies and even policy makers needs to be increased, there must be an adoption of data management culture and skill building in technological infrastructure. The people must be taught to accept data as pathway to development.

Better policies must follow alongside. Policies to efficiently and effectively prosecute corrupt and fraudulent persons or practices in the sector; provide better working conditions and welfare packages for Doctors to reduce the on-going massive exodus of doctors abroad for better opportunities.

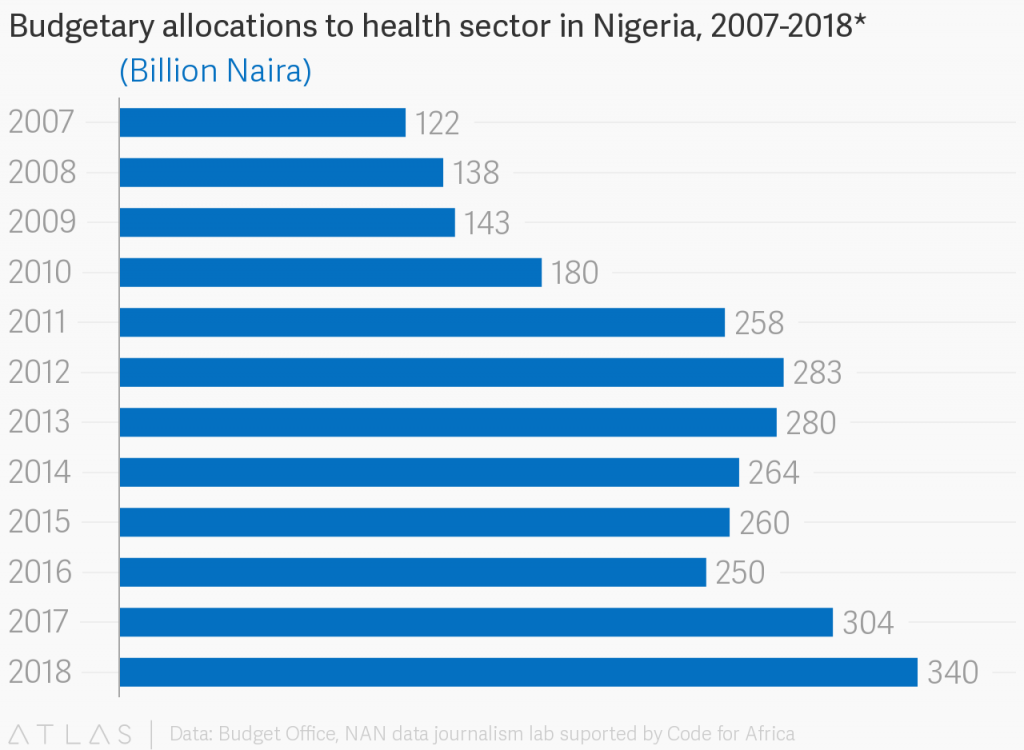

Healthcare funding must be increased. Nigeria’s government allocated N340.45 billion, about 3.9 percent of the N8.6 trillion expenditure plan to the health sector. This is insufficient. Nigeria must do better to commit at least 15 percent of its annual budgets to improving health care services for its citizens.

Data equals building blocks

In founding Orodata a few years ago, I had finally come to an understanding that for Africa to transcend from ‘developing nation’ status, it needed to imbibe data into its culture, this was not negotiable. And that for Nigeria to address its economic and social developmental issues, data literacy was a must, and Open data shouldn’t be a seasonal term or something people mouth at conferences, but rather a way of life for the people, policy makers, and institutions especially. I saw the potentials, I saw that it will improve government effectiveness and allow sectors and regions, policymakers, NGOs, researchers, innovators and private sector dig deep, find anomalies, design solutions, create new economic opportunities, boost citizen trust and inclusion. I also knew that for me, there was no going back in being part of this data movement, this inevitable change. Years after, I am still on the struggle, fighting on with passion. I have garnered experience, a track record and impact to prove. And the surface hasn’t been scratched yet. There’s still so much work to do.

The developed economies of today couldn’t have been in existence without strategies, policies and designs backed up with data. They made data their building block, significantly leveraging insights from it to address unemployment, security, healthcare, commerce, culture, economic growth, safety, traffic, pollution, population growth and many more. Policymakers were able to analyze and refine their regulatory and commercial strategies using data. Problem solvers, innovators and developers co-innovated solutions based on revelations from data while government made decisions with data and ensured the key players had unfettered access to open data enabling them draw insights to address problems and build.

– Blaise Aboh, Founder, Orodata