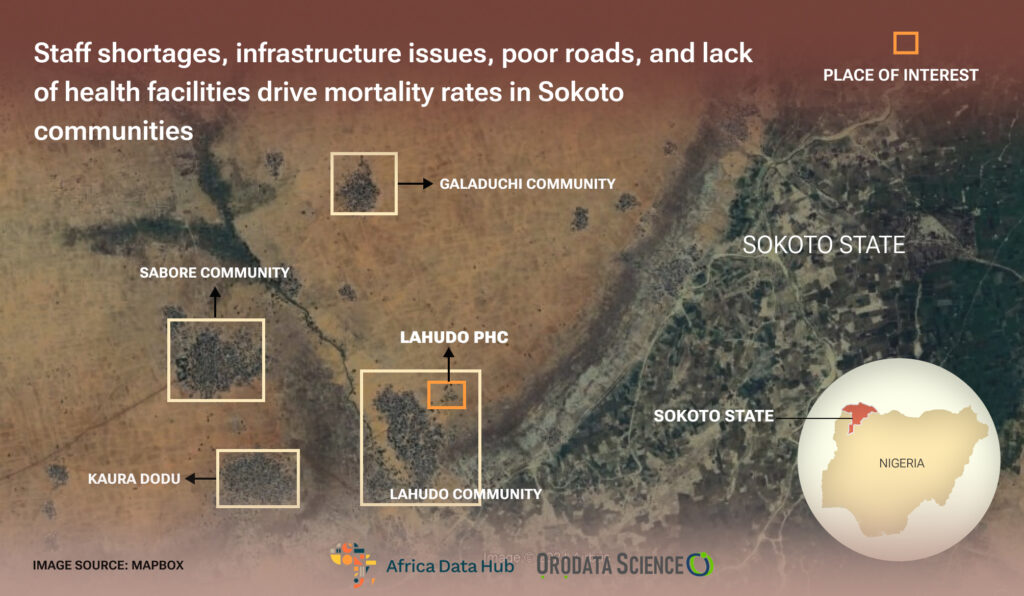

In this story, ABDULRASHEED HAMMAD delves into the dire realities of Primary Health Care services in Sokoto State, shedding light on how staff shortages, infrastructural issues, dilapidated roads, and inadequate facilities contribute to soaring mortality rates in the state.The story also looks at the harrowing experiences of pregnant women, who endure perilous journeys to distant hospitals due to the lack of ambulances and essential health facilities in their local PHCs.

A journey to Lahudo Primary Health Centre is arduous due to the bad road, which can jeopardize pregnancies and complicate patients’ conditions. To reach this healthcare facility, the reporter, fixer, and motorcyclist encountered serious challenges crossing a lake, nearly falling from the motorcycle five times on sandy roads, and amidst large stones before reaching the healthcare center. It took this reporter four days to recover from the body pains he experienced while traversing the road. During the initial visit to this PHC in October 2023, it was found locked; a similar incident occurred during another visit in January 2024, when the PHC was also locked.

During the second visit to the PHC, this reporter’s motorcyclist first declined to go due to the stress he encountered before reaching the healthcare facility the first time his and this reporter visited the place before the reporter persuaded him, and he later agreed to go. This means that in the case of any emergency in Lahudo village at the time this reporter visited the place, the patients or pregnant women had to bear the brunt of the bad road in the process of being rushed to the larger hospital.

An image of a lake that was crossed by this reporter on his way to Lahudo PHC in Wurno

Sadly, primary health care has a staff quarter and an ambulance, but they have stopped functioning. The staff quarters are in a deplorable state, which made the health workers reluctant to live in the village, and the ambulance is useless because it has stopped working.

Image of the entrance of deplorable Lahudo PHC

The primary healthcare is in a deplorable state; the roof is leaking; although there is a fan, there is no electricity to power it; the healthcare, mattresses, and wards are dirty; and the compound is bushy, resembling a deserted place.

Front view of Lahudo PHC

Hauwa’u Nafi’u, a 25-year-old pregnant woman with four children, was rushed to Kware General Hospital three weeks before this reporter visited the place in January 2024 in a state of unconsciousness with a cab. After reaching there, the doctor confirmed that it was not yet time for her labor. She was taken back home after going through a strenuous journey and having additional complications in the process of carrying her on the impassable road. Why did they rush her to a larger hospital instead of Lahudo PHC? It was for two reasons: one was due to the deplorable state of health care, and the second was due to lack of female health workers to assist her.

Hauwa Nafiu, a pregnant woman in Lahudo Ward

“I felt so bad because if our hospital was working perfectly, I wouldn’t have been taken to another hospital. When I was taken to Lahudo PHC, the doctors were not around. That was why I was taken to Kware General Hospital, which is over one and a half hours’ journey from Lahudo. Another problem is that only male doctors will attend to us if we go to the hospital; if possible, there should be female doctors that would be attending us,” she said.

Hajia Kulu Buhari

Fifty-seven-year-old Hajiya Kulu Buhari said there are many residents of Lahudo who have lost their lives before reaching the hospital due to the bad condition of the road and lack of adequate health facilities, citing the example of a lady called Fatimah in her neighborhood who died on the way while being taken to Kware General Hospital for medical treatment. She said pregnant women are facing serious challenges due to the lack of female doctors in health care, adding that many women want to go for antenatal or delivery, but their husbands don’t allow a male doctor to check on their wives.

The entrance of Lahudo PHC

“Our women are doing home delivery, and in the case of an emergency, we have to call the doctors to come; if they don’t come, we have to find a car and carry the patient to the Kware hospital when the ambulance was active, but now that it is not active, we have to find a motorcycle or tricycle to carry her if we have the means; if we don’t have, we don’t have any other option than to stay home and wait for Allah’s help,” she noted.

The deplorable state of the wards in Lahudo PHC

Aminu Abdullahi, 50, the community leader of Lahudo Primary Health Care, also emphasized that women opt for home delivery due to the lack of female health workers. He lamented the breakdown of the ambulance, which has necessitated transporting patients to other hospitals under challenging conditions.

The community leader of Lahudo Ward

He further stated that they wanted the community health workers to stay in the hospital, given the staff quarters’s existence, but they complained about the insecurity and deplorable condition of the staff quarters. He pleaded with the government to renovate the staff quarters to ensure better access to healthcare services.

Sandy Road en route to Lahudo PHC.

Hudu Bako, a community health worker in Lahudo PHC, stressed on the dire lack of medical supplies and personnel in the hospital, emphasizing the urgent need for renovation and additional staff to meet the community’s healthcare needs.

The image of deplorable state of Lahudo PHC

National Emergency Maternal and Child Health Intervention Centre (NEMCHIC) in 2019. The aim was to reduce preventable maternal and child deaths by 50 percent by 2021 through oversight of various health services, particularly focusing on reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health and nutrition (RMNCAH+N) services at primary health care (PHC) at community levels.

Abandoned staff quarters in Lahudo

Identifying delays as major contributors to high maternal mortality, NEMCHIC devised interventions, including the Reaching Every Ward with Skilled Birth Attendants (REWSBA) strategy, aimed at mobilizing and retaining skilled birth attendants (SBAs) at PHC facilities nationwide. However, as of the first quarter of 2022, a significant proportion of PHC facilities in Sokoto State failed to meet the standard of having at least two midwives and two community health extension workers (CHEWs) per facility, particularly affecting rural communities.

The deplorable state of Lahudo PHC Ward like a deserted place

On August 24, 2021, the Sokoto State government, under the Ministry of Health, released over N204 million (N204,511,817.40) to Abbysia Investment Ltd for the upgrade of Sanyinna Primary Healthcare to a General Hospital in Tambuwal Local Government. A visit to the hospital reveals the deplorable state of primary healthcare in the community and the upgrading of the primary healthcare to a General hospital which eventually began in October 2021 was abandoned by the contractor in March 2022.

A ward in Sanyinna PHC in Tambuwal LGA

Residents suffer access to healthcare as Health Ministry Staff abandon multi-million naira health project

The site visit is disheartening; structures intended to usher in a new era of medical care remain unfinished, some not even reaching the lintel level. Staff quarters stand untouched, reflecting the apparent indifference that has befallen this project. Healthcare workers in the facility lament the shoddy workmanship that resulted in leaky roofs and subsequent decay, further amplifying the community’s struggle.

Abandoned building intended for the upgrade of Sanyinna PHC to Sanyinna

General Hospital.

As of 2022, the company had a single director, Mohammed Ango Habibu. On August 3, 2023, the board of directors was expanded to three members, including Mustapha Ango Habibu and Mustahpha Abdulrahman Habibu.

Abandoned buildings in Sanyinna PHC

Findings from the Corporate Affairs Commission portal (CAC portal) reveal that Muhammad, a staff of the Sokoto State Ministry of Health, is the face behind Abbysia Investment Ltd, the company awarded the contract.

Profile picture of Muhammad Habibu on LinkedIn

These actions undeniably contravene section 26(24) and 69(1-11) of the Sokoto State Bureau of Public Procurement Law which says “(24) Any person who has been engaged in preparing for a procurement or part of the proceeding thereof may not bid for the procurement in question or any part of it either as main contractor or sub-contractor-and may not cooperate in any manner with bidders in the course of preparing their tender.”

Non-functioning ambulance in Sanyinna PHC

An infraction of the above law is punishable under section 70(5) which states that; “Any person who will be carrying out his duties as an officer of the Board or any procuring entity who contravenes any provision of this Law commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a cumulative punishment of:

(a) a term of imprisonment of not more than 2 years or N200,000.00 fine

(b) termination of appointment from government service”

Sanyinna PHC Ward and entrance view

Mu’azu Hassan, 25, a resident of Sanyinna Ward in Tambuwal LGA, received a call from his aunt to check on his child, Musbau, who had fallen sick while her husband was away in a faraway village.

building in Sanyinna PHC

Upon arrival, he found the boy in critical condition, and with no available vehicle, he had to rush him to Sanyinna PHC on a commercial motorcycle. Upon arrival at the hospital, two health workers inquired about the child’s condition. Mu’azu explained that the boy’s body temperature had risen significantly, and he was unable to communicate. After examining him, the health workers said that the situation was beyond their capability, and he was subsequently referred to Yabo General Hospital.

Mu’azu expressed frustration over the non-functional ambulance at the PHC, which could have been instrumental in the emergency. After obtaining the referral letter, he carried the boy to the roadside in search of transportation to Yabo. “It usually takes us about 20 minutes from Sanyinna to Yabo, but that day, we encountered numerous challenges,” Mu’azu recounted. “I waited by the roadside for over 40 minutes, anxious and worried for the boy’s condition. At one point, I even considered giving up, but thankfully, we eventually found a vehicle. Sadly, by the time we arrived at Yabo, the child had already passed away,” he lamented.

Mu’azu attributed the tragic outcome to the lack of infrastructure, adequate healthcare facilities, and trained medical personnel at Sanyinna PHC.

Asma’u Usman, 45, a resident of Garam village, expressed distress over the dismal condition of the healthcare facility. She highlighted the absence of electricity and essential medical supplies, along with the discomfort of the facility. Additionally, she mentioned that the facility’s ambulance was non-functional. Umar Muhammad, 44, whose wife is pregnant, shared the challenges they faced due to the inadequate facilities at Sanyinna PHC. He cited the lack of functional toilets, electricity, medical supplies, and ambulances for emergency transfers. The lengthy journey to a larger hospital in case of emergencies added to their ordeal, causing unnecessary pain and financial strain.

The community health worker revealed that Sanyinna PHC suffers from a shortage of essential medical supplies, including syringes, bandages, gloves, and personal protective equipment. Additionally, the lack of a functional ambulance and infusion pump further compounds the challenges. The absence of laboratory scientists and medical doctors exacerbates the situation, despite the reliance of over 10 communities on the PHC for healthcare services.

In Kwargaba PHC, Lack of Health Facilities Expose Patients, Pregnant Women to Further Medical Complications

Locating Kwargaba PHC is akin to Lahudo PHC, albeit without the need to cross a lake. The journey along the road is arduous, presenting a challenge for a healthy individual like this reporter, his fixer, and the bike man. However, it poses a double challenge for a pregnant woman enduring the pains of labor or a patient grappling with complications.

Abandoned Buildings in Kwargaba PHC

The primary healthcare facility is in a state of disrepair. There are no beds available for pregnant women to deliver their babies, and the ward lacks privacy, with passersby able to observe expectant mothers. The roof is dilapidated, and an additional building stands rundown and abandoned.

A day before this reporter visited Kwargaba Healthcare, Amadu Malami rushed his laboring wife to the Kwargaba PHC. Upon arrival, he discovered that the facility does not admit pregnant women due to a shortage of wards and beds. Transporting her to Wurno General Hospital posed a challenge as well, as her critical condition and the poor road made motorcycle transport unsafe.

Amadu Malami

“All our efforts to secure a vehicle in our rural community were futile, leading us to opt for an in-home delivery,” he explained.

Kwargaba PHC Ward

Salihu Muhammad, a 70-year-old man from the Kwargaba community, was rushed to Kwargaba PHC two days prior to this reporter’s visit in January due to vomiting and diarrhea. Although the community health worker tried his best, the severity of the case necessitated transfer to a general hospital. However, due to the lack of ambulances and his critical condition, he remained at home, enduring the pain.

Salihu Muhammad in a state of unconsciousness in his house

“We lack the financial means to arrange transportation to another hospital. That’s why we left him at home without seeking further medical attention,” lamented one of Salihu Muhammad’s sons. Muazu Aliyu, the community health worker at Kwargaba PHC, highlighted the facility’s challenges, including the inability to admit patients due to a slide of beds, ambulances, medical equipment, and drugs. Patients struggle to transport themselves on the treacherous road.

Image of deplorable state of Kwargaba PHC

He recounted an outbreak of cholera in 2021, during which the community was overwhelmed. Lack of space forced them to accommodate over 40 patients per day on the floor. The outbreak, suspected to have been triggered by a woman from Lokoja, Kogi State, claimed the lives of many.

Abandoned Ward in Kwargaba PHC

“We later discovered it was an airborne disease, potentially spread through contaminated water sources. Unfortunately, we lacked the resources to conduct a thorough investigation into its root causes,” he explained.

The outside view of Kwargaba PHC

Another community health worker corroborated the cholera outbreak, emphasizing the challenges posed by a shortage of doctors, medical records staff, and security concerns. Over 25 settlements rely on Kwargaba PHC for healthcare services.

Dilapidated Wards in PHC in Kwargaba

Wurno Secondary School Clinic Becomes home for Cockroaches, Pests, Nine Years After Abandonment

No one could fathom that a healthcare facility could be so devoid of essential elements like wards, beds, windows, or basic medical equipment that would indicate its purpose. This reporter would have doubted its identity as a healthcare facility if not for confirmation from the community health worker in charge, who attested that it had been abandoned since 2015.

Abandoned and Dilapidated PHC in Wurno Secondary School Clinic Facility

The healthcare facility comprises only two wards with leaky roofs, dilapidated structures, dysfunctional toilets, and a conspicuous absence of windows. Since its closure, neighboring villages that once relied on it have redirected their patients to Wurno General Hospital for treatment.

Dilapidated state of Wurno Secondary Clinic toilet

Deplorable state of Wurno Secondary School Clinic Facility

Previously, emergency cases were treated onsite, but now all patients are referred to Wurno General Hospital due to the lack of medical facilities at the PHC.

“Most people prefer to seek treatment at Wurno General Hospital because this place is unsuitable. I only provide prescriptions for students. If a student feels unwell, they come to me for a prescription, as this place is inadequate for medical care. When it was operational, we had everything we needed here, but now, as you can see, there’s nothing—no benches, no equipment, and other essentials. We’ve voiced our concerns to the local government, but they’ve absolved themselves of responsibility, and even the PHC’s toilet is in disrepair,” he emphasized.

Wurno Secondary School Clinic Facility Ward

Usama Aminu, a JSS1 student at Wurno Secondary School, was spotted eating in the abandoned building formerly known as the PHC, unaware of its past use. “But if we fall ill, we simply go to the office and ask the teacher for medication,” he remarked.

Wurno Secondary School Clinic Facility Toilet

Hajia Asabe Balarabe, the Sokoto State Commissioner for Health, said this reporter should reach out to the Executive Secretary of the Primary Healthcare Agency. She clarified that the Executive Secretary is responsible for handling issues related to Primary Healthcare in Sokoto State. On her part, Larai Aliyu Tambuwal, Executive Secretary of Sokoto State Primary Health Care, said this reporter should write a formal letter to the agency before granting an opportunity to interview her. After the letter was submitted to the agency, she said she recently assumed office and finds it challenging to provide a response regarding the steps they are taking to improve the state of primary health care in the state. She noted that all the directors from whom she could gather information have been dropped, and she does not want to provide inaccurate information to the reporter. She added that she hasn’t fully taken over the office and she was not familiar with the programs they were implementing, noting that she was from WHO and lacks complete information about the PHCs in the state. She said: “With the absence of the directors I relied on for information, it’s difficult to give you a response. I hold a strategic position, and any information I provide will bind me. Therefore, I refrain from making statements to avoid any repercussions. “I am accountable for all activities within the agency, and I am cautious not to make statements that will come back to me. I am currently gathering this information, as I have not been actively involved in the system. Previously, I worked at the WHO, focusing on surveillance and immunization. I have just arrived at the office, and it is empty. Please give us time to gather the necessary information.” When the reporter approached the commissioner after Mrs. Larai’s response, she declined to comment, citing the division of departments within the ministry. She insisted that the reporter should communicate directly with Mrs. Larai, adding that they have only been in the system for a few months and do not possess detailed information about the reporter’s inquiries at the moment.

This story was produced for the Frontline Investigative Program and supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.